What is Cancer Immunology?

Chances are, you’ve heard of cancer: a disease characterized by uncontrolled, dangerous cell growth. These abnormal cells, known as cancer cells, spread and damage various tissues and organs.

With almost 20 million new cases and 10 million worldwide deaths per year, cancer is a leading cause of death spurred on by various factors. UV radiation, tobacco, and possibly the artificial soda sweetener aspartame are all carcinogens: substances in our daily lives associated with cancer development. Genetics is also a large factor; when mutations occur at the molecular level, the risk of cancer increases in future generations.

Since the nineteenth century, researchers have been exploring new approaches beyond traditional therapies. One highly promising field is cancer immunology: a branch of science that fights cancer using a patient’s own immune system.

Conventional treatments such as chemotherapy directly eliminate cancer cells. Immunotherapy functions differently; it gives the immune system a boost to independently attack cancer cells. Like a scout, the immune system detects and eliminates abnormal cells before they develop into large tumors.

The Immune System’s Role in Cancer Defense

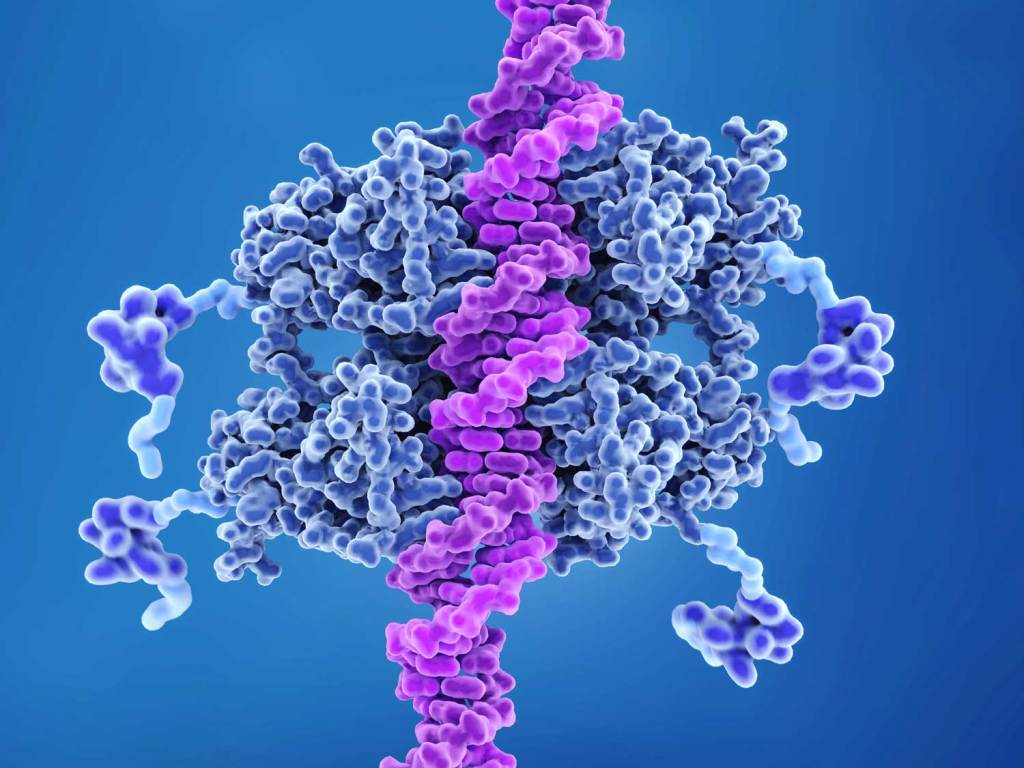

The immune system is made up of cells, tissues, and organs. Like an all-star sports team, this network works together to protect the body against bacteria and diseases. Some of these superstars include T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. While all of these cells are lymphocytes (white blood cells), T cells are most common in immunotherapy.

While immune cells typically destroy any abnormal cells, cancer cells may sometimes evade detection and hinder a proper immune response. Unlike external treatments, cancer immunotherapy aims to fix this by retraining the immune system to target abnormal cells.

Types of Cancer Immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapy encompasses a variety of approaches that each serve different purposes. Some of the most researched forms of immunotherapy include:

Checkpoint Inhibitors: “Checkpoint” proteins help regulate immune response by switching off T cell activity. While checkpoints such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 ensure that healthy cells are not attacked, some cancer cells exploit these checkpoints by expressing proteins to switch off cancer detection. Checkpoint inhibitors are drugs that block these molecules, freeing the immune system to recognize cancer cells again.

CAR-T Cell Therapy: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell therapy engineers a patient’s T cells to express a specific receptor (CAR) that targets cancer cells. Each batch of T cells only targets one antigen (proteins on cells that trigger an immune response). To do this, a patient’s T cells are separated from the blood through an IV. The antigen-specific CAR is then added to the patient’s T cells in a laboratory and grown to produce a large number of CAR T cells. When enough cells are grown for treatment, the CAR T cells are infused back into the patient.

Adoptive Cell Transfer: As the parent approach to CAR-T Cell Therapy, adoptive cell transfer takes T cells from a patient, enhances their cancer-targeting abilities, and then reintroduces them into the patient’s body. One application is Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (TIL) Therapy, where T cells from tumor tissue are activated in the laboratory. In another method, T cells are grown in the lab and examined to isolate T cells with the strongest immune response. In both cases, these cells are infused back into a patient.

Therapeutic Vaccines: Like CAR-T cell therapy, these vaccines stimulate the immune system to recognize specific antigens. Unlike CAR-T cell therapy, these vaccines are administered by needle, like an annual flu shot. Therapeutic vaccines reintroduce antigens into the body alongside a substance known as an adjuvant. This is because, for many therapeutic vaccines, antigens alone do not generate a strong enough immune response. As a result, substances known to enhance immune responses (immunopotentiators), such as dead viruses or aluminum salts, are added to the vaccine. When the immune system attacks these adjuvants, it also targets the cancer antigens with them; this causes a chain reaction that kills cancer cells lurking in the body.

Future Projects

While recent immunotherapies have shown positive results in trials, leading to long-term remissions in patients with seemingly untreatable cancers, challenges of tumor resistance still exist. A concern about autoimmune side effects also remains, requiring further study. However, scientists hope to address these concerns in years to come.

Even at the high school level, cancer immunology research shines bright. At Western Reserve Academy, ongoing research explores multiple facets of cancer immunology, including therapeutic vaccines for T-cell lymphoma and glioblastoma, non-neurotoxic adjuvant alternatives, and chemical treatments.

As technology advances, research in cancer immunology offers renewed hope for patients and their families worldwide. With the next critical breakthrough, cancer might just be a thing of the past.

Leave a comment