What is Subculturing?

Scientists often grow cells outside of their usual living environments through cell culturing.

Cultured cells secrete toxins, but they don’t have ways to get rid of their waste. Scientists must monitor conditions in the lab to make cells grow as efficiently as possible; this is accomplished via subculturing. Although there are many different ways to subculture based on cell type and growth method (plates, slants, broths, etc.), one of the most common is splitting cells suspended in a liquid medium, which WRA students use in their Cancer Immunology courses.

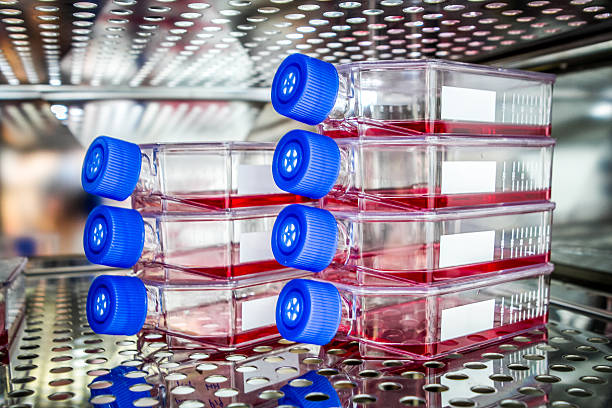

During subculturing, also known as cell passaging, cells are transferred from crowded containers, each dense with hundreds of thousands of cells, to fresh containers, creating more growing space. This is necessary to avoid exhausting nutrients in the liquid, accumulating waste, and initiating “contact inhibition,” when cells make contact with one another and stop growing. Think of this like being squished on an airplane; if you’re too close to your neighbor, there isn’t ample space to spread out or sit comfortably.

Cell Confluency:

The key to subculturing is the confluency of cells or the estimated amount of cells in each flask or culture plate. Confluency is measured by observing the percentage of surface area covered when observed under a microscope. Typically, researchers begin to subculture when cells reach an optimal percentage of about 80%, but this percentage varies by cell type.

The Process:

Working with cells in sterile environments is crucial, so researchers use protected hoods to block out contaminants and always keep their hands and other materials clean while working.

First, cells must be removed from the container by removing the media containing the cells. If the cells adhere, or stick to the container, researchers use a dissociating buffer to detach them. It is important to disturb cells as little as possible, avoid having them sit without liquid, and work quickly during this process to keep cells alive.

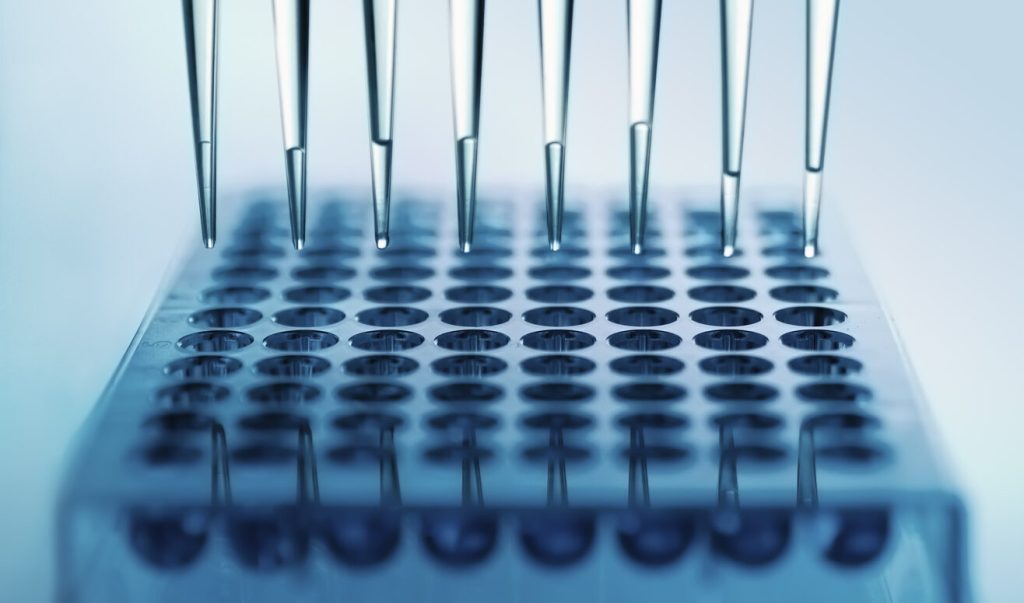

All cells taken out of the flask are still suspended in liquid, which is transferred into a tube and placed into a centrifuge. Centrifuges apply a strong rotational force to “spin” cells and isolate them in a singular pellet at the bottom of the tube, which has a cone-shaped bottom, separating the pellet from the liquid above.

The remaining liquid contains no cells and can be discarded, while the cell pellet is saved and mixed with fresh medium. After using a pipette to resuspend the cells into liquid, the suspension is placed into two containers and combined with new growth medium. While resuspending cells, researchers create “single-cell suspensions” by pipetting up and down and moving the liquid through a small opening at the end of the pipette to break it apart.

After subculturing into two new containers, the cells can be placed back into an incubator, and they will continue to divide until it’s time to subculture again.

– Isabella Haslinger Johnson ’25

Leave a comment